The Australian Political System: Key Ideas, Institutions and Debates

Taught and designed by Associate Professor Gwenda Tavan

In this foundational political science unit we examine the nature and evolution of the Australian political system and contemporary political culture. This includes examining the fundamental ideas that the system was supposedly founded upon, tensions within and between those ideas, and how these translate into practice across each part of the system. These lines of analysis provide the foundation for regular discussion of what types of reform are required to improve the quality of our political system and how that reform might be achieved. The course is tertiary (i.e. university level) in nature and teaching staff are both well qualified and experienced (for more information see here). However, you do not need to be connected to a university or to have previously studied political science, political economy or economics to enrol.

Design: The subject is taught in ‘flipped classroom’ mode whereby you first view an online lecture, then undertake some suggested reading, and then participate in a weekly 90-minute class (with a short break at the 45 minute mark) where we discuss set questions as well as field any queries or comments you wish to contribute.

Tutorial sizes have a maximum upper limit of 19 people (usually less) in order to generate a conversational, easy-going and genuinely interactive experience. The lectures and readings are all downloadable and may be done whenever you like. The lectures can either be viewed, or simply listened to as podcasts. One-on-one help is provided whenever you need to clarify anything.

Commencement date and discussion group time(s)

This subject will run in the second half of 2023 in Term 3 and/or Term 4. You will likely be able to choose between in-person and online discussion sessions.

Group discussion sessions are 1.5 hour in length (with a 5-minute break at the halfway mark). Other sessions times on different days (and different times of the day) may also be offered.

Cost (major currencies list below, contact us for costs in other currencies)

Australian Dollars AUD$250 (waged), AUD$200 (unwaged).

US Dollars US$170 (waged) US$130 (unwaged)

Euros EUR160 (waged) EUR130 (unwaged)

UK Pounds GBP140 (waged) GBP110 (unwaged)

Payment can be made via electronic funds transfer, credit card or PayPal. All students are eligible for a full (and no questions asked) refund if they change their mind about undertaking the course if they can provide notification within 10 days of registering.

Assessment: There are regular questions and answers to allow you to self-test your knowledge, but the results of such self-tests are only available to you. Tutorial discussions are also a great opportunity to test and clarify your ideas. As already mentioned, you can get one-on-one assistance via email, phone or zoom to confirm (or clarify) any aspect of the course.

Accreditation: The purpose of the course is to provide you with a high-quality, accessible, university-level subject rather than to provide formal accreditation in the form of a degree, certificate or similar. However, you can certainly gain a level of knowledge that matches similar courses taught at university and if you undertake and complete the course, you can obviously list that you have done so on your resume, and we are able to provide verification of your participation and engagement with the subject.

WEEK 1 UNDERSTANDING AND ASSESSING LIBERAL DEMOCRACIES

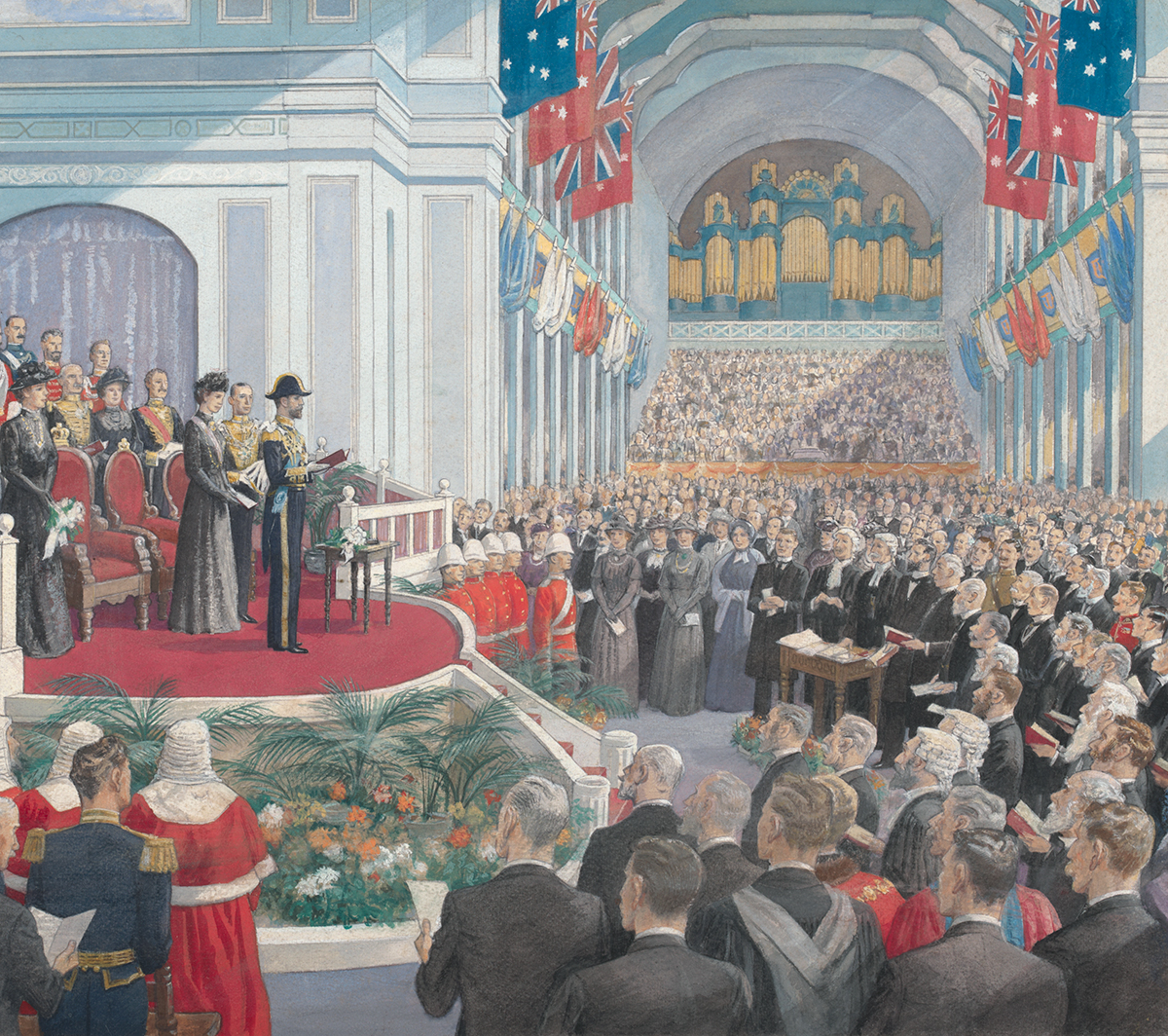

In 1901 Australia was founded as a liberal democracy. The democratic tradition assumes that all citizens have equal opportunity to participate in the political system, and that governments must be representative of and responsible to the people they govern. The liberal tradition is concerned with limiting the power of the state over individuals, society and the market economy. The focus this week is on examining democracy and liberalism, with a particular focus on their complementarities and tensions in both theory and practice.

WEEK 2 AUSTRALIA’S HYBRID CONSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK

Australia’s constitutional arrangements are sometimes referred to as the ‘Washminster System’ because they combine elements of the British Westminster system, premised on the political supremacy of a representative and responsible parliament, and U.S. style federalism which divides power between national (federal) and state governments. We consider Australia’s constitutional framework and the tensions and anomalies created by combining two distinct, sometimes contradictory, systems of government, embodied most dramatically in 1975 when Governor-General Sir John Kerr sacked the democratically-elected Whitlam Labor government.

WEEK 3 THE EVOLUTION OF AUSTRALIAN FEDERALISM

While the Constitution specifies how power and responsibility are divided between the federal and state governments, there has nonetheless been considerable evolution in the power balance between these two levels. We examine this ongoing evolution and what has driven it. That analysis provides the basis for a discussion of how federalism might be improved in ways that reduce wasteful duplication, inefficiencies and unfairness while also being consistent with a system structurally designed to provide multiple forms of representation and to protect minority interests.

WEEK 4 THE COURT SYSTEM AND JUDICIAL ACTIVISM

An independent judiciary that is separate from the executive and legislative arms of government is crucial to sustaining liberal democracies, as it protects individuals and organisations from excessive and arbitrary government interference. This week we focus on the role of the courts in Australian politics, with particular emphasis on the High Court and its power to interpret and rule on whether other actors in society are acting in a manner that is consistent with the constitution. This includes an analysis of various landmark and controversial rulings it has made in recent years. Do these rulings demonstrate that the High Court has gone beyond its constitutional authority and is undermining strongly held principles of the separation of powers or does it demonstrate that the court is in fact upholding them?

WEEK 5 RESPONSIBLE PARLIAMENTARY GOVERNMENT

The Westminster system of responsible parliamentary government is an important building block of liberal democratic government in Australia; placing great emphasis on collective and individual responsibility to keep governments accountable to the parliament, and ultimately to the people. Despite this emphasis, many of the parliament’s powers and responsibilities are not codified in law or the Constitution, relying instead on informal rules and conventions that have developed over time to function. The evolution of strong party discipline, combined with changes to how political offices are staffed and operate, has meant that parliamentary practice and power now operates quite differently from how it was designed and intended. After examining the various factors that work against responsibility, accountability and transparency in the parliament, we examine what might be done to improve the situation.

WEEK 6 EXECUTIVE GOVERNMENT

The executive branch of government has the responsibility of implementing or executing the law. While executive authority in Australia actually rests with King Charles of England and is exercised on his behalf in Australia by the Governor-General, in normal day-to-day practice executive authority is exercised by a Cabinet of ministers that is headed by the Prime Minister. Cabinet authority has increased in recent years to the point where some suggest that ‘responsible executive government’ rather than ‘responsible parliamentary government’ is a far more accurate description of the system. The growing influence of the Prime Minister within and outside of the Cabinet also has implications for how the system functions. We examine the various factors that have driven this centralisation of power and what should and could be done in response.

WEEK 7 THE ELECTORAL SYSTEM

The capacity of citizens to elect representatives via popular vote is a widely accepted cornerstone of democracy. Opinion is divided, nevertheless, about which type of electoral system delivers better outcomes. The specific details of the electoral system can make an enormous difference to who gets elected, how elected officials behave and what policies end up being enacted. For example, some voting systems make it almost impossible for minor parties to win seats. Others actively encourage it, promoting power-sharing arrangements in government as a means of enhancing democratic representation and accountability. We examine the specific mechanics and consequences of both the preferential and proportional voting systems in Australia. We contemplate how these systems might be refined, or even replaced by alternative voting methods, to enhance liberal and democratic rights.

WEEK 8 THE PARTY SYSTEM

While parties, party government and party systems are fundamental features of all modern democratic political systems, they can have quite diverse characteristics, influenced by factors such as electoral systems and the historical, cultural, and political environment in which they have developed. This week we look at the evolution of Australia’s party system in the House of Representatives and consider both the causes and political impact of the increasing numbers of minor parties and independents being elected to both Houses of Parliament.

WEEK 9 EXTRA-PARLIAMENTARY ACTORS (INTERESTS AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS)

Interest groups and lobbyists are key actors in the Australian political system. Indeed, there is increasing disquiet about the growing influence of such actors in the political process, given they are primarily concerned with sectional rather than collective interests. Social movements, which are more amorphous in character, and tend to be values-driven and socially focused, rather than narrowly self-interested, are also significant entities. We examine how these groups interact with governments, parliament and political parties, and consider the question whether their influence enhances democracy (because it provides opportunities by ordinary members of civil society to engage with the formal political system) or undermines it (because it pushes special interests and/or minority causes).

WEEK 10 THE MEDIA AND POLITICS

The media plays a crucial role in modern democracies, communicating ideas and information between parliamentarians and electors, and providing a key forum for the public to observe and participate in political debate. Its ability to expose, highlight and critique wrongdoing by the state is also critical to the effective operations of the system, by keeping elected representatives accountable.

The media is also a powerful political actor in its own right, because of its subtle (and sometimes not-so-subtle) capacity to set political agendas. It does this by giving prominence to certain issues and viewpoints or ignoring or downplaying others. With one of the greatest concentrations of media ownership in the world, much of it related to one of the largest, wealthiest and most overtly political media organisations in the world, concerns are often expressed that corporate media interests are undermining Australian democracy. While the proliferation and diversification of media created by technological advances (including social media) has slightly blunted this threat, it has also greatly enabled the circulation of misinformation and ‘echo chambers’ that confirm and seldom challenge people’s pre-existing ideas on politics. We examine various lines of analysis behind these problems and discuss possible solutions.